brokenbiscuits

Books of 1916: Part Four

Books of 1916: E.F. Benson Edition

Freaks of Mayfair by E.F. Benson

E.F. Benson is one of the most reliable writers. He always serves up something tasty. Freaks of Mayfair is not a novel but a series of comic sketches of the kinds of “freaks” who lived in Mayfair, an area of London that I know mainly as one of the properties on the Monopoly board; I believe it is dark blue.

This book made me kind of cross with E.F. Benson but then I love E.F. Benson so I felt bad about that. In the end I wound up feeling sympathetic to him as well as sorry for him.

I thought the highlight of this book would be his sketch of Aunt Georgie, who will reappear later as Georgie Pillson in the wonderful Lucia books. In the Lucia books, Georgie lives in the fictional town of Tilling, doing his needlepoint and playing cards with Lucia and Miss Mapp and all the other colorful town characters. Eventually Georgie and the title character Lucia make their platonic relationship official by embarking on a marriage in name only.

Unfortunately, the “Aunt Georgie” sketch was the lowlight. While I don’t think E.F. Benson would have self-identified as gay (anyway, how could he, having died in 1940?), he is famous for his romantic friendships with other men, etc, so I felt let down to see his portrayal of Georgie was on the vicious side. The last thing anyone needs to read is a humorous skewering of someone who was born “an infant of the male sex according to physical equipment, but it became perfectly obvious even when he was quite a little boy that he was quite a little girl.” In a way it gives a little frisson of “I am seen, I exist” to see an Edwardian character who “formed a violent attachment to another young lady, on whom Nature had bestowed the frame of a male, and they gave each other pieces of their hair... and they probably would have kissed each other if they had dared.” But I hate that Georgie has to be a figure of fun.

“Public-school life checked the outward manifestation of girlhood, but Georgie’s essential nature continued to develop in secret. Publicly he became more or less a male boy, but this was not because he was really growing into a male boy, but because through ridicule, contempt, and example he found it more convenient to behave like one.” Depressing. But I think I’m starting to understand the enduring nature of the confusion between gender identity and sexual orientation (for example, when people get transgender people and gay people mixed up.) The original reason for this confusion is purposeful: sexual orientation could not be named at this time but it was okay to say Georgie was a woman. The “problem” is not really who you like, it’s who you are, hence all this tedious focus there still is on “same sex relationships” which throws everything back on yourself when you thought it was about how you felt about other people. Alternately, perhaps E.F. Benson really did conceive of Aunt Georgie as a (transgender) woman: because of the customs of the age, it’s impossible to tell.

“[Although] he did not care for girls in any proper manly way, he liked, when he was sleepy in the morning to hear the rustle of skirts.” “[H]is guests were chiefly young men with rather waggly walks and little jerky movements of their hands and old ladies with whom he was always a great success, for he understood them so well.” “Occasionally, for no reason, he roused violent antagonism in the breasts of rude brainless men, and after he had left the smoking-room in the evening, one would sometimes say to another, ‘Good God! What is it?’”

On the plus side, Georgie leads a happy life, drawing pictures and being arty and visiting with his friends. We should all be so lucky. At the end of the sketch, Benson points out that Georgie has never hurt anyone and that it would cruel to send him to hell, but it would be “very odd” for him to be an angel in heaven. The whole book has a light satirical tone, but it was meaner in the Georgie sketch than all the others. But clearly, as with all hating people, E.F. Benson hates himself (again, back to self, who you are is the problem.) Before reading this book I always thought that Georgie was Benson. Fred is trying to draw some kind of line in the sand between himself and Georgie. Oh, Fred is not like Georgie because Fred is quite butch! That’s where I started feeling so sad for Fred Benson and why did he have such terrible misfortune to be born in Victorian England to pious parents instead of (for example) in New York in the 1970s to atheists? And wouldn’t E.F. Benson be fun to have around if he were alive today?

Moving on to the more entertaining parts of the book, it was much more amusing to see Benson hating on his brother, who is skewered in “The Spiritual Pastor.” I mean, I don’t even know that much about the Benson family but even I could see it has to be his brother. All the other freaks of Mayfair have something unusual and undesirable about them, except for this vicar, whose undesirable quality is that he’s too good looking, too good at sports, too well-liked, too upbeat, too humble. What really makes writer Benson gnash his teeth is how successful the vicar is with his writing career, publishing commonplace religious essays. The examples of the kinds of things the vicar writes were fun, because they were exactly the same as some uplifting self-help type stuff you might read today (eg don’t be so upset about being late for the train, pay attention to the fluffy clouds in the sky!) But honestly not even bad enough to make fun of. Pure sibling rivalry!

There were other examples of things the freaks did that Benson thought were totally ridiculous which today are commonly accepted, such as practicing yoga and having a vegetarian diet. But yoga practitioners are not members of a persecuted minority, so it didn’t make me get all up on my high horse to read the “Quack quack” sketch. The chapter where I actually felt personally most skewered, and found most hilarious, was “The Eternally Uncompromised” about a person with too much imagination, just like me. Winifred Ames’ particular problem was always imagining that men were looking at her with eyes of silent longing. (She read too much sentimental trashy literature from the circulating library, same as Miriam in Backwater.) But Winny-Pinny’s greatest dream, of being talked about as being in a compromising situation with a man who’s not her husband, recedes from her as fast as she chases it. “Indeed, it is receding faster than she pursues now, for her hair is getting to be a dimmer gold, and the skin at the outer corner of those poor eyes, ever looking out for unreal lovers, is beginning to faintly suggest the aspect of a muddy lane, when a flock of sheep have walked over it, leaving it trodden and dinted.”

Other quite funny sketches are about snobs, social climbers, and older people who cling to their lost youth (“grizzly kittens.”) Just once Benson alludes to the war, saying “the myriad graves in France and Flanders bear a testimony [to the manliness of the British, maybe the war is why he has this topic on the brain] that is the more eloquent for it being unspoken.”

I noticed how often in my book reviews I start out by saying, “I expected x, y, and z to happen, but...” or “I thought it would be the same as n, but...” (In this case, expecting the sketch of Aunt Georgie to be the best part.) Or occasionally I say, “Just like I expected, such-and-such happened!” If this habit is tedious for me, it must be tedious for you. Is there any way I could stop having expectations about novels, and stop making up a projected plot the instant I lay eyes on it? I would really like it if that could happen.

David Blaize by E.F. Benson

Naturally, E.F. Benson published three books in 1916. Most of his books took him three weeks to write. He described himself as “uncontrollably prolific.” His biographer suggests that the whole Benson family’s prodigious output is due to mania. I say, a preferred kind of mania if you could pick and choose.

I didn’t read Mike but I read David Blaize many years ago. This is today one of Benson’s most popular novels. It is a boarding school story. I enjoy those, and it has everything you want in one, including terrifying but secretly kind headmasters, beatings, cricket, and lots of pranks. The heart of the story is the friendship that the title character develops with an older boy named Maddox. The most memorable part is when Maddox is ogling David in the shower, David doesn’t like it and leaves, and Maddox comes to apologize to him. Then later another character is expelled for bringing disgrace onto himself for writing love letters to another boy. Maddox says that it could have been himself and that David has made him “uncorrupt” himself, and David thanks Maddox for shielding him from filth. Because they have chosen the path of purity, they then basically get to have a love scene, lying next to each other on the grass, wriggling shyly closer, feeling intense happiness, and then playing sports. Forever after they are the greatest of friends. David and Maddox get to hold hands at the end because David almost dies (of injuries from heroically stopping a runaway horse on the high street.) A brush with death is the only situation where males are permitted to hold hands, and one of them has to be delirious or unconscious. I think you could read every book on the planet and never find a more striking example of an author desperately trying to repudiate sexual feelings and at the same time elevate the purity of love between two boys. When I read David Blaize as a young person it just made me roll my eyes, but as a withered-up middle-aged person I find it very touching and a bit sad.

According to Benson’s biographer Brian Masters, David Blaize was the first positive treatment of a romantic friendship at a boy’s school and while it was a critical success it was “dangerously new.” E.F. Benson’s brother Arthur wanted him to leave all that stuff out but Fred didn’t listen. So Fred received lots of fan mail about the book, including one from the Front saying “the lads in the trenches are sharing it and passing it around.” Masters says Fred would “not have been pleased to learn that the novel is still on the list of homosexual book clubs” and that “it does not belong there.” (This biography was written in 1991.) So Masters and I have opposite ideas about how Fred would feel if he were re-animated, and that is because no one knows. (Who is this guy Brian Masters anyway? He also wrote biographies of a serial killer and necrophiliac, a wicked zoo owner, British dukes, and Marie Corelli.)

Years later Fred said, “I have had more correspondence about [David Blaize] than any other book I ever wrote. That I think has been because there was no ‘book-making’ about it, but it was a genuine piece of self-expression.” And now we have a pleasing moment where I actually agree with both Brian Masters and the guy who wrote the introduction to Freaks of Mayfair, Christopher Hawtree. They both say that 1916 was a turning point in Benson’s development as an artist, as he stopped writing those unconvincing sentimental romances centering on a man and a woman, and began writing the comedies he is now known for. I think it is the fact that Benson is writing about things he actually cares about (in his peculiar way) that makes both David Blaize and Freaks of Mayfair so appealing and yet painful. (I don't mean peculiar in a bad way. He is one of a kind. He sort of has no heart, but usually in a kindly way, and how can someone be kindly with no heart? So it must be there but he is very coy, plus clearly he is not motivated by the same things as most other people. You go read some E.F. Benson and you'll see.)

Two years earlier Benson’s brother Hugh (the Catholic one) died of pneumonia, and in 1916 his sister Maggie died of heart troubles. Based on Final Edition, one of E.F. Benson’s memoirs that he completed just days before his own death, it looks like during 1916 all the extant members of his family were suffering from mental illness or just about to die themselves. So it’s really remarkable that Benson could be so funny and was only about to get funnier.

I’m going to read Final Edition and the slightly annoying biography more carefully instead of just skimming for the good bits. And I should probably read at least one of his other memoirs too. Then I’ll be fully ready for his two novels of 1917. I’m glad I have many more years with E.F. Benson before he dies of throat cancer in 1940. His best books are yet to come!

Books of 1916: Part Three

Books of 1916: Part Three: Natsume Soseki and James Joyce

Light and Darkness by Natsume Soseki

This unfinished novel, which was serialized in a newspaper, was Natsume Soseki’s last work, as he died of an ulcer in 1916. As the story begins, the main character Tsuda is going to have an operation on his intestines that sounds incredibly unsound and unclean. Think of the horrible and bizarre medical care we get today and then imagine it 100 times worse! So I was really worried about what was going to happen to Tsuda and felt that he was putting his head in the sand by worrying about his money troubles and his relationship with his wife, etc. But it turned out that the book really was about those things. Tsuda’s illness and operation ended up seeming more metaphorical than an important plot point.

I’m sorry to say that I really struggled to get from one end of this book to the other. I adored Natsume Soseki’s other books Kokoro and Grass on the Wayside. They were so lovely and brilliant. But he didn’t get a chance to edit this book and get it into shape, plus it sounds like he was sick and worried the whole time he was writing it. The afterword said that some critics consider this novel a “postmodern masterpiece” precisely because it is unfinished. But it wasn’t the lack of ending that did me in, it was the whole middle of the book, which dragged and was hard for me to focus on. I liked hearing from the point of view of Tsuda’s wife, O-Nobu, except that it went on and on without resolution. I also liked seeing all the period details of Japanese life, especially now that I’ve actually been to Japan.

Tsuda was a little bit like the main character in Grass on the Wayside in that he didn’t have very good social skills and tended to say things that made people feel bad without meaning to. The story really picked up at the end, when we finally learn Tsuda’s secret, that he has never gotten over the woman he used to love, and he goes to see her in a sanatorium, sort of like the one in The Magic Mountain except Japanese of course. His pretext is that he’s recovering from the surgery and he wants to take the waters, but naturally I was wondering if his pretext would turn out to be the truth and he would never leave. This was the section that I enjoyed the most but of course it came to an abrupt end.

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce

When I think of James Joyce, I always think of three people in my life who felt very strongly about him. First was my mother, who was a big James Joyce fan and talked to me a lot about him. Second, a boyfriend I had who was also a big Joyce fan, and we used to read bits of Stephen Hero and Ulysses out loud to each other. Third, my wife Aine, who had been forced to read some Joyce in secondary school in County Clare and absolutely hated him, and all other Irish writers she read in school (except Oscar Wilde.) She said they were all pretentious wankers. Early on, I had to work hard to convince her that James Joyce was not a Protestant, as she had lumped him together in her mind with Synge, Yeats, Shaw etc. In fact, just now when I read her this paragraph to see if she endorsed my characterization of her views, I had to persuade her once again that Joyce was not Anglo-Irish.

I read Portrait of the Artist As A Young Man in 2002, sure that I was going to love it as much as I loved everything else I’d read by Joyce. And indeed I was hooked by the opening page (“When you wet the bed, first it is warm and then it gets cold.”) I loved reading about the childhood of this sensitive boy Stephen Dedalus, and how his family argued at the dinner table about Parnell, and all about the scary priests who ran everything. But then I got to the part where Stephen starts going to prostitutes at around the age of fifteen, and I was completely bewildered and grossed out. Then he catches religion and becomes devout. Then he starts rabbiting on about art and aestheticism.

I had utterly lost sympathy with the protagonist and the author. Not only that, this Stephen Dedalus character began to remind me incredibly strongly of the Joyce-worshipping boyfriend, whom I had just broken up with weeks earlier. They were both totally pretentious and couldn’t keep it in their pants! (This is the same boyfriend who would get me so angry, the one I mentioned earlier in my review of These Twain. He’s certainly getting a harsh edit in these book reviews. Who knew he was so inextricably linked to 1916? He did have many good qualities, which were not at the forefront of my mind when read Portrait of the Artist.)

I ended up despising this novel. I bet if I re-read it now having had more life experience, I would have a more gentle and forgiving eye, but I probably never will. (Also, what kind of person likes Stephen Hero but not this one, when Stephen Hero is just an earlier draft of the same book? I think it’s pretty clear that the problem was mainly me, or mainly the ex-boyfriend.) I do get another chance to give James Joyce a fair shake in 1918 with his play Exiles.

I inherited my mom’s copy of this novel. It’s all marked up with notes, including D.H. Lawrence’s assessment of Joyce—“too terribly would-be and done-on-purpose, utterly without spontaneity or real life”—to which I say, people who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones. Much more magically, this copy contains photographs of me and my mom and Aine. Look at how happy we all were back then! These were from my birthday, in 2010 or even earlier.

Books of 1916: Part Two

Books of 1916: Part Two

The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

Since childhood I’ve been familiar with the plot of this short novel; people talk about it all the time because it’s so compelling. I even had the first sentence memorized thanks to my older brother. Reciting it was a warm-up exercise in some sort of theater class he was in, except for some reason they added an extra word, making it: “When Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from unpleasant dreams, he found himself changed in his bed into a monstrous vermin sofa.” And yet I had never even read one word of The Metamorphosis before now! It was so much more awesome than I was even expecting. So dark and weird and sad but a little bit funny.

Gregor realizes straightaway that he has become a monstrous vermin, but he’s mainly worried about how he will get to work on time and what would happen to his family if he lost his job. I was thinking, oh Gregor, you’re worried about the wrong thing, you just can’t face what your real problem is. But you know what? He absolutely was worried about the correct things. It’s becoming more and more clear that I’m the one who’s always worried about the wrong thing.

My wife wanted to know what does this story mean, on a metaphorical level. I never think about stuff like that. But I think it is a metaphor for being a lowly creature trapped living at home with your parents. Gregor is the ultimate back bedroom casualty. He literally can't leave his room after he transforms into a bug. Also it's about humanity, and the way we treat the Other, including non-human animals. Gregor is the one who is no longer a human, but his family are the ones who treat him so cruelly without sympathy or understanding, even his sister who started out being the caring one.

Understood Betsy by Dorothy Canfield

I can’t even remember when I first read this; presumably as a child. I think it deserves a much greater reputation as a children’s classic than it has. It’s about a little orphan girl, Elizabeth Ann, who is being raised by her two overprotective, uptight, city-dwelling aunts. Poor Elizabeth Ann is frail and vaguely sickly and afraid of everything, just like her aunties who “understand” her and smother her with love. When a family illness means she must be sent away to stay with another branch of the family who live way out in the country, she is terrified. But she blossoms as she encounters nature, animals, having responsibilities, doing things for herself, and especially her brusque but kind, plain-spoken new family. Elizabeth Ann (now Betsy) begins attending a one-room school house that amazingly seems exactly like a Montessori school, and she makes friends for the first time. The part where Betsy is left behind at the Fair, and the ending where Betsy must choose where she is going to live, elevate this book into a masterpiece.

Rinkitink in Oz by Frank L. Baum

I love the Oz books. Rinkitink is a jolly king with a talking goat who has to go on a dangerous journey with young Prince Inga. As a matter of fact, they’re not in Oz but in a nearby fantastical land. Prince Inga has three magical pearls that guide him, and he tries to hide two of them in the pointy toes of his shoes. But the shoes get thrown away and then they’re really in trouble. You think you won’t see Dorothy but at the last minute she and the Wizard and Ozma show up to save the day.

Usually you can count on the Oz books to leave out the racist garbage that is so prevalent in the books of this time period, but there was a horrible bit at the end of this one that I had forgotten which involves transforming the talking goat back into Prince Bobo of Boboland, and there’s even an illustration. If I were reading this book out loud to a young child I would skip over that part.

Unfortunately there aren’t that many Oz books left as L. Frank Baum is due to die in 1919. Do you think I should keep on reading the sequels by Ruth Plumly Thompson, who took over the series after Baum’s death? I have a couple years to make up my mind.

Backwater by Dorothy Richardson

The second in Richardson’s modernist, stream-of-consciousness novels about an English girl who has to become a teacher because her family has fallen on hard times. There are thirteen of these books and the series is called Pilgrimage. Last time she was working at a German boarding school, and this time she is at an English school. I love the way the main character Miriam’s mind works. Her romantic mooniness is so real and relatable. The most touching part was when she discovers a lending library where she can read the complete works of Ouida, which have always been forbidden to her because they’re too smutty. This novel really shows how when you have a rich inner life you will find splendor and meaning somewhere, even in the most depressing or banal surroundings. Unfortunately there’s a section when she’s on holiday at the seaside and there are some musicians who are described with the n-word repeatedly.

Leatherface by Emma Orczy

Just like last year, the Baroness is the only one who takes the horrors of war head on. Again it is historical fiction, set in Belgium (who wouldn’t feel for brave little Belgium in 1916?) during the Spanish Inquisition. A dashing hero known only as Leatherface because of the mask he wears has been protecting the Prince of Orange and doing other brave deeds for the cause. Fans of Baroness Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel series won’t be surprised to learn that it is the lazy, good-natured, tavern-loving man about town character who is actually Leatherface, or that the female protagonist is torn between her family duty to unmask Leatherface and her love for him.

A bit of altar diplomacy has brought Leatherface and this beautiful Spanish lady together into a marriage in name only, but it turns out to be one of those things where they fall in love after they are married. (I asked my brother if there was a name for this trope, and he suggested A Convenient Marriage since Georgette Heyer wrote at least four novels on this theme and one of them was called A Convenient Marriage.) I ate all this intrigue up with a spoon. But the bulk of the novel is about the horrors of war and people getting killed, killed, killed.

In the end, the town of Ghent escapes complete annihilation but the people allow Spanish supervillain the Duke of Alva to go free. “Perhaps they had suffered too much to thirst for active revenge,” is the book’s closing line, which I found unexpectedly pacifistic and moving. Also hats off to Emma Orczy for FINALLY laying off the anti-Semitism for one entire book except for a single one-liner.

Books of 1916: Part One

Books of 1916: Part One

2016 was a tough year in many ways, so may I introduce you to 1916? I think you’re going to love 1916.

I was struck by something I read in a (very nice) review of one of the books of 1916: —“because anything first published in 1916 that does not contain a word or thought about the First World War has got to be interesting.” Yes, you’d think so. But actually most of these novels make no mention of the war whatsoever. They tend to be historical, or escapist, or completely surreal.

You may notice that I’ve only reviewed about half as many books as I did last year for 1915. But last year I wasn’t done until March! So what you are losing in volume you are gaining in punctuality. Basically I began to feel this project was affecting my brain perhaps a little too much. My brother pointed out that I said in casual conversation, “I read that book in 1911.” I needed to dial it down just a bit.

Uneasy Money by PG Wodehouse

PG Wodehouse is always a delightful treat. I’m so happy there are more than fifty books still to come! I went by the US publication date in order to include this book, which some may consider cheating.

Lord Dawlish has a title but no money, so he is delighted when an eccentric millionaire leaves him all his money just because Lord Dawlish (aka Bill) gave him a few golf pointers once. But when Bill discovers that the eccentric millionaire has stiffed poor but deserving relatives, he sets out for Long Island to try to set things right. There is beekeeping, romance, people pretending to be other people, and lots of hilarity. The only sad part is something that happens to a monkey. In the end, everyone ends up engaged to the right person. On the final page we are at the train station in Islip, Long Island, which today is a gross and unappealing town, but apparently 100 years ago was a bucolic spot where the rich built mansions. If this book doesn’t make you smile, your soul is in mortal danger.

These Twain by Arnold Bennett

This is the third book in the Clayhanger series, and my favorite. In These Twain, the somewhat-starcrossed lovers from the first two books, Edwin and Hilda Clayhanger, embark on married life. They fight a lot. I read this book in the 1990s and haven’t re-read it, but what I remember most vividly are the descriptions of how angry they get at each other. Edwin Clayhanger thinks how he’d like to strangle Hilda, but then he goes for a walk and after a while he calms down, and when he comes home, he loves her again. At that time I was dating someone who made me really angry fairly often, and I thought These Twain was incredibly realistic. Bennett’s World-War-I-themed book (The Roll-Call) will come up in 1918, and is the last in the Clayhanger series.

Love at Second Sight by Ada Leverson

My hardcore fans (yes, both of you!) may remember that two years ago I was unable to review Birds of Paradise because I mislaid it and therefore couldn’t read it. (It turned up in the end, in a knapsack I never use.) I was eager to rectify my mistake by reading Ada Leverson’s 1916 offering, especially as this was her last novel.

Love at Second Sight is the last book in the Little Ottleys trilogy. Although I didn’t read the first two, it was easy to see what must have happened in them—in book one, the main character Edith must have married her husband, and then in the second one both Edith and her husband fall in love with other people but remain together thanks to Edith’s bloody-minded loyalty.

As this novel opens, Edith’s family has a guest in the house, and it’s unclear who she is, why she’s come to stay, and how long she plans to be there. But Madame Frabelle exercises a strange fascination over all of them. This book is terribly amusing and I’m not even going to tell you what happens, other than it’s a scream. The protagonist is thinking funny things about other people all the time but since she’s kind and fairly quiet, people don’t realize that she’s amusing and smart. The husband seems like the most annoying person on earth, and he must be drawn from life because how could you invent a person that annoying?

This is one of the rare books that has a contemporary setting during World War I. The husband was not called up because of a “neurotic heart,” which seems to be like PTSD. Edith’s love interest from the previous book returns home from the war, wounded. This novel’s realism allowed me to see all kinds of period details. For example, when the characters need to look up train timetables, they use things called the ABC and Bradshaw, which must be the apps they had on their phones at that time. Edith also had an Italian composer best friend who I thought might be based on Puccini since (according to Wikipedia) he and Ada Leverson were great pals.

I really was on the edge of my seat wondering what would happen, and guess what? Everyone gets a happy ending!

Ada Leverson’s Wikipedia page says cattily that after this novel, she worked on ever-smaller projects. Just like me!

Inclinations by Ronald Firbank

Firbank is a riot! This book reminds me a bit of Morrissey’s List of the Lost. Of course, that should be no surprise really, since both of them are directly related to Oscar Wilde on the literary family tree. What sets them apart is Inclinations is unalloyed comedy and nearly all dialogue.

What kind of inclinations does this novel concern itself with, you may ask? Well, it’s about a middle-aged writer Miss Geraldine O’Brookmore, known as Gerald, who brings a fourteen year old girl (Miss Mabel Collins) on a trip to the Mediterranean. There’s basically no description of anything or explanation of what’s happening or who is speaking, so you have to be okay with feeling unsure about what’s going on. One of the characters is shot and killed and it was chapters later that I finally understood which one. Plot is not what this book is about. This book is about lines so funny and with such a nice ring to them that I will just give you a small sampling for your enjoyment:

Miss Collins clasped her hands. “I’d give almost anything to be blasé.”

***

“I don’t see Mrs Cowsend, do you?”

“Breakfast was laid for four covers in her room.”

“For four!”

“Or perhaps it was only three.”

***

“She writes curiously in the style of one of my unknown correspondents.”

***

[Talking about a costume ball]:

“Oh, Gerald, you could be a silver-tasselled Portia almost with what you have, and I a Maid of Orleans.”

“You!”

“Don’t be tiresome, darling. It’s not as if we were going in boys’ clothes!”

***

“Once she bought a little calf for some special binding, but let it grow up...and now it’s a cow!”

***

“Gerald has a gold revolver. ‘Honour” she calls it.”

***

“Is your father tall?”

“As we drive I shall give you all his measurements.”

***

“I had a good time in Smyrna,” she drowsily declared.

“Only there?”

“Oh, my dears, I’m weary of streets; so weary!”

***

“I’m told she [Gerald] is a noted Vampire.”

“Who ever said so?”

“Some friend of hers—in Chelsea.”

“What do Vampires do?”

“What don’t they!”

If you find this sort of off-putting, these lines really do make more sense, somewhat more sense, in context. In a chapter that is eight words long (“Mabel! Mabel! Mabel! Mabel! Mabel! Mabel! Mabel! Mabel!”), Miss Mabel Collins throws off the protectoress-ship of Gerald and elopes with a count. The final section of the book is different, slightly more conventional and somewhat Jane Austen-esque (“I’ve such news!” “What is it?” “The Chase is let at last.”) In this part, the Countess (Miss Collins-that-was) returns home to England with her toddler and there’s question in some minds about whether she is properly, legally married. I’m looking forward to Firbank’s next novel in 1917.

I’m only just now realizing that Firbank is the author that the main character keeps reading in The Swimming Pool Library by Alan Hollinghurst. I guess I thought Alan Hollinghurst just made him up. The thing is that his name sounds so made up, just “Fairbanks” with some of the letters taken out. Ugh, I learn everything backward.

Oscar Wilde

World War I

Alan Hollinghurst

Arnold Bennett

Ada Leverson

Ronald Firbank

PG Wodehouse

Morrissey

Uneasy Money

1916

list of the lost

these twain

inclinations

the roll-call

love at second sight

books of 1916

islip

clayhanger

little ottleys

neurotic heart

puccini

a noted vampire

swimming pool library

Oscar Wilde

World War I

Alan Hollinghurst

Arnold Bennett

Ada Leverson

Ronald Firbank

PG Wodehouse

Morrissey

Uneasy Money

1916

list of the lost

these twain

inclinations

the roll-call

love at second sight

books of 1916

islip

clayhanger

little ottleys

neurotic heart

puccini

a noted vampire

swimming pool library

Books of 1915 (Part Five)

The Rainbow by D.H. Lawrence

I loved Sons and Lovers, and who doesn’t love “The Rocking Horse Winner”? So I figured I would like this one too. The Rainbow follows several members of a family through different generations. They live on a farm in the East Midlands of England. There was something incredibly irritating about this novel. I couldn’t quite put my finger on it, but as I was reading it, I was inwardly wailing, “Wheeeennn will this be oooover??” There were a lot of men who didn’t know how to interact with others or have real relationships, especially with women, which I guess is stark realism but was frustrating for me to read. Also, I have no problem with florid prose per se, just this wasn’t doing it for me. One highlight was a grisly alcoholism-related fatal farming accident.

The last family member was a young woman, Ursula, who has a bleak and depressing relationship with another women. You would think I would like that part but I think it was too dark for me. Then she has a bleak and depressing job as a teacher at a brutal school, which degrades Ursula so much that at one point she just loses it and starts hitting a student. And she has a bleak and depressing relationship with a man. Apparently I have blocked out what happens in the end.

Luckily, when I complained to my brother about this elusive annoying quality in The Rainbow, he told me that Kate Millett had gotten to the bottom of D.H. Lawrence in her legendary book Sexual Politics. So, here is what your auntie Kate has to say:

Millett explains that Lawrence is suffering from womb envy, which I would back her up on, and that the “new woman” (like Ursula) intimidates him. She points out that the chapter where Ursula has an affair with another woman is called “Shame,” which I actually didn’t even notice. (Sometimes I am so steeped in my own attitude that I can’t even imagine what the author intended, which has advantages and drawbacks.) Millett also paid attention to what happened at the end of the novel, unlike me, which was: Ursula fails her university exams and becomes a contented housewife. Millett chalks up the irritating quality of The Rainbow to an underlying sexist oinker agenda. BTW, I am not supposed to be reviewing the books of 1969, but Sexual Politics is nothing like what I expected. I had no idea that it was mostly literary criticism!

Anyway, I’m not sure if I can handle Lawrence’s sequel, Women in Love, but I am intrigued by the 1922 offering Aaron’s Rod. With a title like that, what could go wrong?

Still to come-Unread

The Voyage Out by Virginia Woolf

I know, I know; why didn’t I read this one? I think I was a little intimidated so I was putting it off. I know Virginia Woolf is super famous and this is probably actually the best book of 1915, so I really will read it.

Psmith, Journalist by P.G. Wodehouse

I am perpetually one book behind in the Psmith series, so I haven’t read this one yet. Here is my brother’s review:

“In the third novel about Mike and Psmith they visit New York, where Mike prepares for a cricket match. Psmith befriends Billy Windsor, the sub-editor of the children’s journal Cosy Moments. Billy is fed up with the treacly material it is his job to edit, so when the editor goes on vacation Psmith persuades Billy to revamp the journal. The current contributors are all fired and Cosy Moments features a new column about the pugilist Kid Brady and a hard-hitting series about tenement slumlords. It is unusual for PG Wodehouse to focus on the dark underbelly of capitalism, but he does so in his own way. When a criminal syndicate pressures Psmith to stop publishing the tenement exposé, he declares “Cosy Moments cannot be muzzled.” It is nice that Mike is not the slightest bit jealous of the relationship between Psmith and Billy, and at the end of the novel Mike and Psmith return to England, where they conclude their saga in Leave it to Psmith, a novel of 1923.”

The Oakleyites by E.F. Benson

Thanks heavens my brother read and reviewed this book for me too! As follows:

“The Oakleyites chronicles the lives of the leisure class of the seaside village of Oakley, apparently based on Rye, where E.F. Benson lived. Here we see the Dante classes, picture exhibitions and amateur piano recitals encountered subsequently in his more famous Mapp and Lucia novels. Among the Oakleyites are three middle-aged sisters, each a devotee and exponent of vegetarianism, Yoga and Christian Science, respectively. Their rivalries are as funny as anything Benson ever wrote. The difference from Benson’s later novels is that the Queen of Oakley society, Dorothy Jackson, is a romantic heroine. She falls in love with the author of facile novels about Marchionesses when he moves to Oakley with his mother on account of her health. Dorothy dreams of inspiring him to write a really worthwhile novel (apparently this was a very common aspiration a hundred years ago). I wanted to give Dorothy a little hint: “girlfriend, there’s a reason this guy is still living with his mother at the age of thirty-five!” But Benson apparently felt he could not tell the real story...”

Vainglory by Ronald Firbank

I got this out of the library but it’s due back soon. Firbank’s Wikipedia page says he was an openly gay man who was very inspired by Oscar Wilde, and “an enthusiastic consumer of cannabis.” So that sounds like fun!

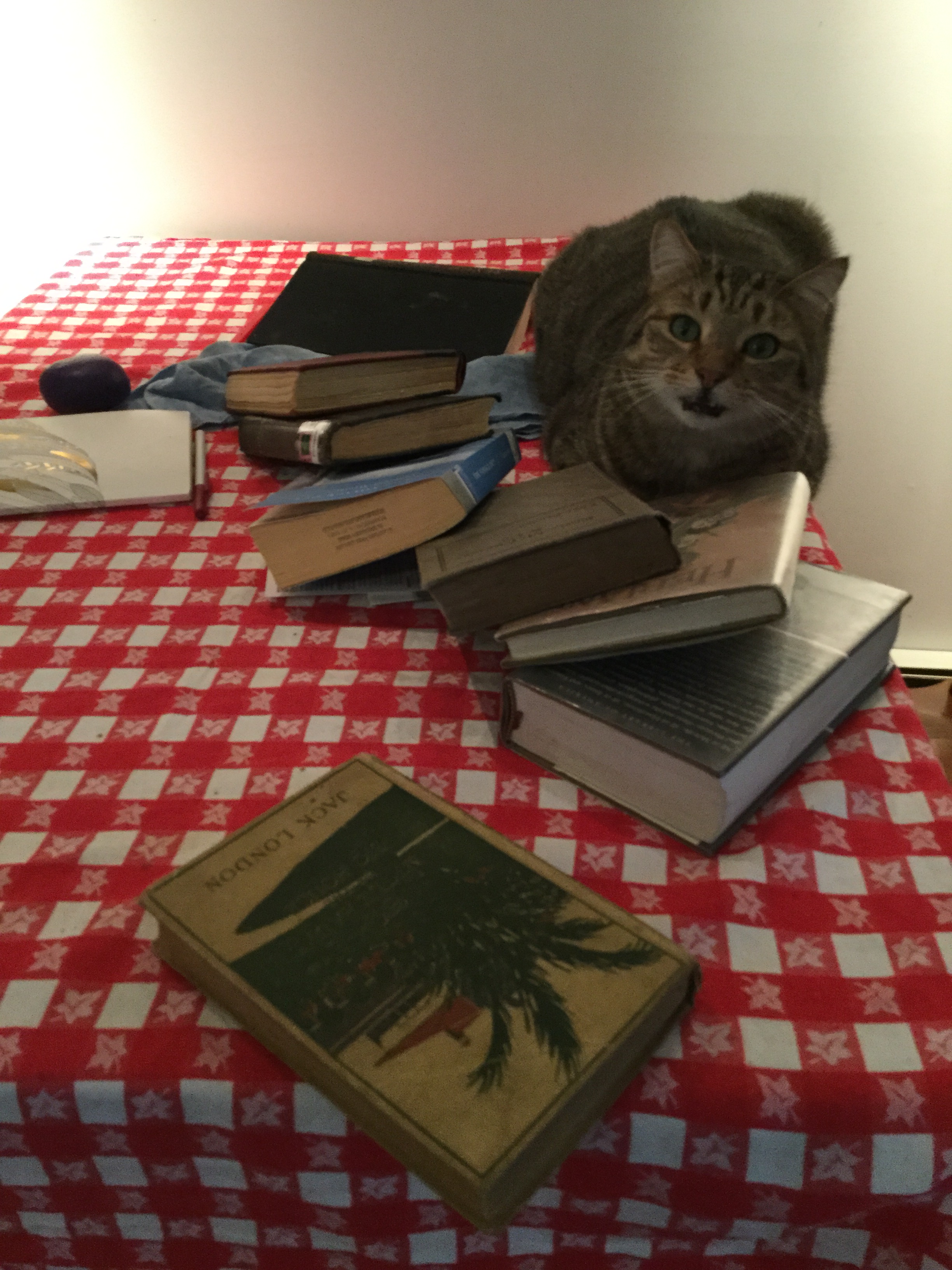

The Little Lady of the Big House by Jack London

This is about a love triangle. I bought this novel but, I’m going to be completely honest here, I will probably never get around to reading it. 1916 beckons!

Will Never Read, and why

The Genius by Theodore Dreiser

The Titan was tough going last year. As described on the Wikipedia page, The Genius is a semi-autobiographical novel about a man who is unable to remain faithful and his “affair” with a teenage girl and then his wife dies in childbirth. I just couldn’t face it.

Boon by H.G. Wells

This is a satirical novel written under a pseudonym in which Wells lampoons his former friend Henry James. I was interested to read about it, but didn’t want to read the actual book.

The Return of Tarzan by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Look, there are over 20 more of these books to come. I’m sure I’ll read another one at some point.

That's all! See you in 1916!

Books of 1915 (Part Four)

“Sansho the Steward” by Mori Ogai

This is a poignant short story about a brother and sister who are kidnapped and sold into slavery. There’s no way there could be a happy end for both of them.

The Golden Slipper, and other problems for Violet Strange by Anna Katherine Green

A fun detective novel! The detective is a beautiful, rich, popular heiress. So why is she solving crimes simply to make money? Her special ability is to understand people’s characters. There was a single thread or plot about Miss Strange running through it, but it was also a series of basically stand-alone mysteries. The cases started out being the kind of crimes a society girl might potentially encounter, like a missing necklace, but became increasingly more atmospheric and gothic, involving hidden chambers and tunnels and caves and spooky old houses with dozens of clocks and a blind doctor who is a top gun shooting ace.

The Good Soldier by Ford Maddox Ford

I read this when I was a teenager and I don’t remember it well, just that it was about a group of friends who are having marital problems. I remember that the real story was revealed somewhat slowly, and that I liked it. I looked it up just now on Wikipedia to make sure I was even thinking of the right book, and I learned that Ford originally wanted to call it “The Saddest Story.” His publishers asked for a new title (very properly, in my view—I don’t want to read a book called “The Saddest Story”) and as a joke he came up with “The Good Soldier” in view of the war. I can only ever think of a joke title for my books too, so I really identify with this.

The Lost Prince by Frances Hodgson Burnett

A poor little boy lives in London with his beloved father, who is working to return to the rightful king of his homeland to the throne. You may have figured it out from the title, but in the final pages of the book the boy is astonished to discover that his own father was the missing heir to the throne. I liked that there was a plucky character with a disability who neither died nor was cured; actually, that character reminded me a bit of Becky from A Little Princess. Not Burnett’s very best book, but I enjoyed reading it.

Dear Enemy by Jean Webster

This is the lesser-known sequel to Daddy Long Legs. In this epistolary novel, Judy, a rich socialite with lively and original ideas takes over the orphanage that the Daddy Long Legs heroine grew up in. I was charmed to learn that the orphanage is in Dutchess County, where I live. The orphanage is cheerless and unhealthy when Judy arrives, but she manages to transform it into a place where the children can have nice clothes, affection, a gentle education, up-to-date (for the period) medical treatment, and the chance to play outdoors. It’s understood that Judy will just run the orphanage for a little while, and then marry her rich boyfriend and stop working forevermore, but later Judy is not so sure. Judy comes into conflict with the orphanage’s crabby Scottish doctor, the “Enemy” of the title. However after a while their animosity turns to friendship and then to...? But the doctor is guarding a sorrowful secret.

This part of the book mirrors Jean Webster’s real life. I don’t know much about her, but I did read her Wikipedia page from top to bottom. In addition to being a supporter of women’s suffrage and various reform movements and education for women, she had a boyfriend who couldn’t divorce his wife because she was mentally ill. (I hear this story over and over, and yet I never hear about the undivorcable mentally ill husband.) Webster’s boyfriend also had a “mentally unstable” child. And it sounds like the boyfriend was not the picture of mental health himself.

Anyway, the least appealing part of Dear Enemy is the lip service granted to the eugenics models of Galton and Goddard, with discussion of the feebleminded Jukes and Kallikaks. Judy eventually concludes that there’s nothing in this heredity business, but because it was the “scientific” idea of the age, Webster gave eugenics quite a bit of air time. It does seem that the whole question of inherited mental illness was one that she had a real personal interest in, and I think she was honestly trying to figure it out rather than just being sensationalistic.

This is one of the books of 1915 that’s still read today, as a fluffy fun book for young people, not as a towering literary classic assigned in school. I think the reason for its endurance is that the main character is spunky and is more like a contemporary woman in terms of her attitude toward education, career, and love.

Victory by Joseph Conrad

An Englishman whose business concern in Asia (I think Indonesia?) has failed ends up living “all alone” on an island. (Actually, he has a servant and in addition the native inhabitants of the island live there, but he is quite isolated.) But when he rescues a musician who is being abused by her boss and brings her back to the island to live with him, the boss hires thugs to exact a horrible revenge. This novel was suspenseful and weird. I think Conrad managed to say something racist about every ethnic group on earth, but it wasn’t as bad as I was expecting. Spoiler:

(show spoiler)

I never read any Conrad before except for “The Secret Sharer” which I quite liked and the first few pages of Lord Jim. But the way everyone talks about him, I was expecting something very dreary and “important.” Instead it was the sort of shlocky melodrama that I enjoy. So I will definitely read his next offering.

The Thirty-Nine Steps by John Buchan

I always liked the Hitchcock film, and the book it is based on is fairly similar. It’s a thriller about a man who has to clear his own name by catching the real killer, and in the process he unmasks a ring of spies, with a lot of picturesque running through the Scottish highlands. There’s an extended soliloquy by one of the characters about Jews who control finance and the world (“The Jew is everywhere, but you have to go far down the back stairs to find him... to get to the real boss, ten to one you are brought up against a little white-faced Jew in a bath-chair with an eye like a rattlesnake.”) I’m not sure if the reader is supposed to take that seriously or think it’s ridiculous, but it was rather creepy.

Books of 1915 (Part Three)

Knulp by Herman Hesse

Knulp is intelligent and witty and everyone likes him, but he has turned his back on having a career or a home or any of the conventional trappings of success. Instead he travels around, sleeping in fields and visiting friends. Because he’s so happy and charming, he has friends all over, and they’re all happy to shelter their vagrant pal for a little while. The novel was told from several different points of view and depicts different periods in Knulp’s life. As he gets older, it becomes clear that sleeping rough has taken its toll and that Knulp is not long for this world. He revisits his home town, which I found very touching. Then he has a philosophical conversation with god about his purpose in life, before lying down in the snow to sleep. The god business is SO not my kind of thing, but it was actually really well-done and I found it quite moving. The “cheerful wanderer” seems to be a “type” from this period. (For example, Maud Hart Lovelace’s Betsy is constantly talking about The Beloved Vagabond, but I don’t think I will ever read it because it is from 1906 and I’m certainly not going to make it to 2106.) This type is valorized in Knulp, but skewered in another book of 1916, I Pose.

The Valley of Fear by Arthur Conan Doyle

A top-drawer Sherlock Holmes novel! It has Professor Moriarty, a secret society, a long backstory, lots of contradictory clues... you can’t ask for more.

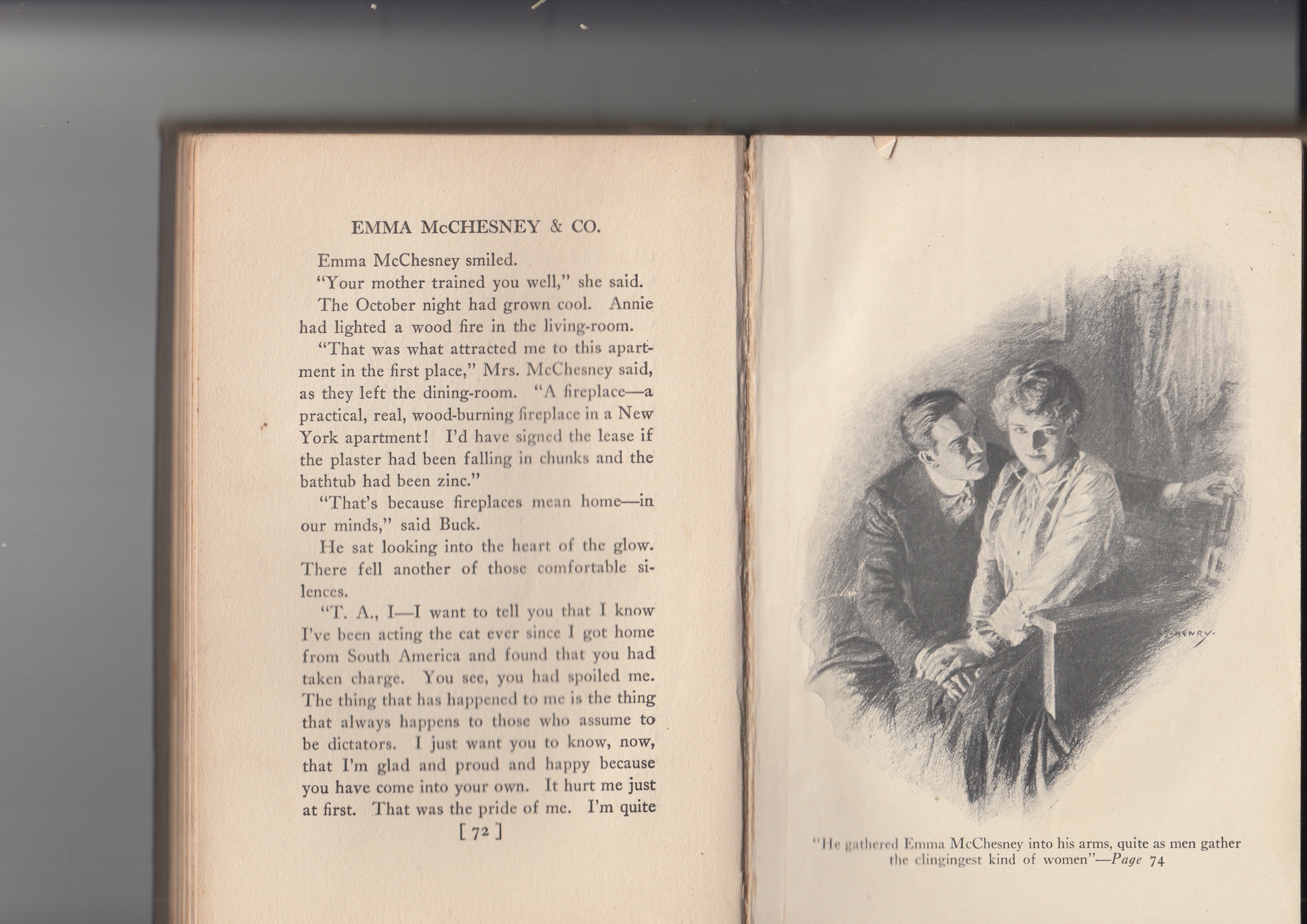

Emma McChesney and Co. by Edna Ferber

The longtime fans of my reviews (like, um, my brother and no one else) will remember that I adore Edna Ferber’s Emma McChesney series. So I’m not even sure how good this book even is, all I know is that I loved it. The best part is how closely this novel mirrors my recent life. Emma McChesney travels to Bahia and Rio, Brazil—just like me! Then she goes to Buenos Aires, Argentina—just like me! Then she meets Miss Morrissey—just like me! Oh no wait, that didn’t happen to me. Anyway, after a triumphant voyage selling a line of petticoats, she returns home and finally deigns to marry T.A. Buck, the head of the petticoat company who’s been courting her for the last two books. Then she spends three months in marital idleness, shopping on Fifth Avenue and attending important dinners, but she can’t stand it and returns to work at the petticoat company. This was a very subversive message for 1915, but Edna Ferber slides it right down your throat before you’ve even noticed. The most fun part is when a dowdy rich girl comes to the factory to lecture the shop girls on dressing respectably, but instead a nice Jewish working girl gives the rich girl tips on clothes and advises her to marry the poor man she loves. Unfortunately, it looks like this is the last Emma McChesney book.

Polyanna Grows Up by Eleanor H. Porter

Remember how bad Miss Billy Married was? So actually I didn’t read the famous one last year, Pollyanna, just this sequel. Polyanna is an inspirational little orphan girl who has been cured of some kind of disability, and has been sent to cheer up a bitter old rich lady. Polyanna is continually playing “the Glad Game,” where no matter what kind of horrible thing has just happened, she will find something to be grateful for. This drives everyone totally bonkers, obviously, but eventually they all swallow the Kool Aid and become incredibly cheerful in the face of life’s adversity. Polyanna is mono-maniacally focused on her Game, so that she comes across as a bit unhinged. A sign of trauma?

Just this very day, my wife was telling me about a concept of acceptance she learned about from an Enneagram teacher named David Daniels, called an attitude of gratitude. But you’re not supposed to concur, condone, or capitulate to bad things that are happening. Polyanna is concurring, condoning, and capitulating all over the place. I’m not sure if I can explain what I mean, but there’s a reason Polyanna is one of the most infamously annoying characters in literature.

Polyanna finds an orphan boy with a disability for the bitter old rich lady to adopt. The lady thinks he might be her missing nephew but she can’t be sure; however, she decides she loves him either way.

Then we fast forward ten or twelve years and our author is presented with a problem. It’s cute (maybe) to have a child constantly playing the Glad Game, but in an adult it would be insufferable. Eleanor Porter actually does a pretty good job of turning Polyanna into a semi-normal human being, considering the situation Porter had created for herself.

Now the book gets a little bit fun, as a few love triangles develop, with many comical misunderstandings about who’s in love with whom, à la Three’s Company. There’s a part that’s really bizarre where Polyanna is almost gored by a wild boar (I think I’ve got this right.) But the one who really suffers from this mishap is the orphan boy with the disability, now also all grown up, because he was unable to rescue her, and he makes a big production out of it. Like many children’s book authors of this era, Porter really has a bee in her bonnet about disability. In the end, everything is sorted out—the orphans all come into their rightful inheritance and everyone is paired off with the right person.

I Pose by Stella Benson

I had high hopes when I began this novel as it has a strong opening. It’s about a highminded young vagabond known only as “the gardener” (because he tells people some claptrap about how the world is his garden) and a woman known only as “the suffragette.” The author explains frankly that these people are poseurs who don’t know how to be their true selves, and they wander the world disapproving of everyone and trying to be avant garde, unable to have authentic relationships with anyone, including themselves. I guess there have always been people like this, and there are certainly still people like that today. The author also promises that even though one of the main characters is a sufragette, it’s not “one of those books,” which made me feel relieved after my bad experience with Delia Blanchflower last year. But she lied! It is one of those books.

I Pose completely falls apart when the characters alight on a Caribbean island that is an English colony. This is the most racist book I have ever encountered—it makes Tarzan of the Apes and Penrod look real good. Reading this novel, I felt unclean. I don’t really want to get into the details, but I will say, I think a lot of times people have this idea that racist English people from a century ago were just old-fashioned but meant no harm; it was all kind of a misunderstanding, god love ‘em. I Pose makes it clear that this rosy assessment is not the case—one hundred years ago, racists hated black people with vicious cruelty and made fun of everything they could think of about them and literally did not care if they lived or died.

There was a kinda interesting part at the end where the suffragette goes into a poor neighborhood in London and tries to get the women to unionize, leave their alcoholic and abusive husbands, etc. but all her schemes backfire. This bit seemed heartfelt and true to life. Now I’m going to go ahead and spoil the ending, since I don’t recommend this book anyway. The gardener and the suffragette decide to get married, but instead, the suffragette shouts, “I hate god!” and runs into the church and blows it up, killing herself. The end. What??

I looked up Stella Benson on Wikipedia to see what was her deal, anyway, and it turns out she was a feminist and a suffragette (it wasn’t clear from the novel which side she was on) and that she lived all over the world, including China and Vietnam. From her bio I would think oh, I can’t wait to read a book by this neglected woman writer but having read this novel I say, never again, Stella Benson, you deserve to be forgotten.

Books of 1915 (Part Two)

Of Human Bondage by W. Somerset Maugham

It has been quite a few years since I read this novel, but I thought it was absolutely terrific and I remember it vividly. The story opens when the main character Philip is a lonely young boy with a club foot being raised by his aunt and uncle. As soon as he is old enough to get away, he moves to Germany and then France where he decides to become a visual artist. That part was extremely interesting to me, as it seemed that, although art and education and customs of every kind have changed so much in the last hundred years, the inner work and the shame of “becoming an artist” have not changed in any way. It seemed very fresh and relevant. There is a “Least Likely To” type of girl who falls in love with Philip and dies by suicide.

Phillip decides that he doesn’t have what it takes to be an artist either, so he returns to London to study medicine. There he meets a server at a restaurant who is incredibly toxic. He falls in love with her and is completely under her sway, supporting her when she gets pregnant by another man. He seriously needs to get himself to a meeting of Codependents Anonymous! I won’t spoil the whole story but let me just give you a couple of key words: “sex work” and “syphilis.” But you will be happy to know that Philip eventually finds happiness and even love.

“The Love Song of Alfred J. Prufrock” by T.S. Eliot

This poem is perfect, and I don’t even know what I could possibly say about it. The back of the copy of The Wasteland and Other Poems that I have says “Few readers need any introduction to the work of the most influential poet of the twentieth century.” So there you go. I remember when I was a kid I liked the way the poem is so interior (as in, the interior of someone’s head), and how it was about someone who was getting old, and I just liked how it sounds. My mom used to recite and read this poem to us and I can still clearly hear in my mind just the way she would intone

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table;

Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets,

The muttering retreats

Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels

And sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells:

Streets that follow like a tedious argument

Of insidious intent

To lead you to an overwhelming question. . .

Oh, do not ask, "What is it?"

Let us go and make our visit.

In the room the women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo.

and then later:

I grow old . . . I grow old . . .

I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled.

Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach?

I shall wear white flannel trousers, and walk upon the beach.

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.

I do not think they will sing to me.

She explained to me that when you’ve had certain kinds of dental work you don’t dare to eat a peach.

T.S. Eliot is an example of someone who was a horrible bigot but who managed to keep it out of his poetry (as far as I’m aware.) I wish Baroness Orczy and some others could be more like that. I’m psyched for more modernist poetry to come!

Grass on the Wayside by Natsume Soseki

I really enjoyed reading this. It was almost as great as Soseki’s 1914 book Kokoro. It’s about a middle-aged curmudgeon who doesn’t know how to get along with anyone, especially his wife and his family. This curmudgeon had been adopted into another family as a child, which was apparently a common Japanese custom of the period, but later the adoption was reversed and he returned to his original family. Now his onetime adoptive father has resurfaced, unsuccessful and unsavory and grasping for money, and our curmudgeon isn’t sure what the right thing to do is. According to the introduction, the story is autobiographical and the main character is supposed to be a very close match to Soseki. But I don’t understand how that can be—how could anyone who has social skills as poor as the main character have the insight to present the situation the way the author does? If the author were really as blinkered as the main character, there’s no way he could have written this book.

I’m looking forward Soseki’s next book in 1915. But oh no! It’s his last one!

A Bride of the Plains by Baroness Orczy

As you may know, I’m a big Baroness Orczy fan. This year I have to give her credit for something very special: although basically the entire world is embroiled in war, she is the ONLY author to address this. She was the ONLY one to write about war, and in Hungary in the Carpathian basin, more or less where all the trouble began. (Okay, I guess there’s also Mariano Azuela writing about the Mexican revolution. But still, props to the Baroness!) I know the production schedule for publishing a novel is pretty long, but a lot of these Edwardians wrote two books a year, and I do think some of them could have at least acknowledged in some way, even thematically, that there’s a world war going on, a pretty big deal! (PS. Are they still Edwardians? What am I supposed to call them now? Baroness Orczy ain’t no modernist!)

Anyway, no one seems to set their novels in the present day, and in fact Baroness Orczy is no exception; A Bride of the Plains is set in what seemed to me like a non-specific time in the past. But the book’s opening takes a pretty clear anti-war tone. It’s almost the day when young men in this little burg are conscripted into the army, a sad day for all:

On this hideous day all the finest lads in the village are taken away to be made into soldiers by the abominable Government? Three years! Why, the lad is a mere child when he goes—one-and-twenty on his last birthday, bless him! still wanting a mother’s care of his stomach, and a father’s heavy stick across his back from time to time to keep him from too much love-making.

Three years ! When he comes back he is a man and has notions of his own. Three years! What are the chances he comes back at all? Bosnia! Where in the world is that? My God, how they hate it! They must go through with it, though they hate it all-every moment.

By the way, I realize that there is probably a glut of war books coming down the pipe, and in a few years I’ll be very nostalgiac for the kind of books I read this year.

Anyway! This is the story of a girl, Elsa, who tries to be true to Andor, the boy she loves who’s been sent off to war. But when it seems that he’s been killed, she knuckles under to her mother’s pressure to marry the bad-tempered richest man in town. But on the eve of her wedding,

(show spoiler)

The downfall of this book is the same problem that Orczy always has: anti-Semitism. Usually it’s just a few throwaway descriptions, but here the villains are an Evil Jew and Evil Jewess. Kind of ruined the book. That’s the whole thing about bigoted people; they just can’t let it go. If you hate Jews so much, Emma Orczy, why don’t you just stop writing about them? But no, she can’t help herself! Maddening. I will say that there’s a lot of suspense and action in this book, if you can get past the bad taste in your mouth.

The Underdogs (Los de Abajo) by Mariano Azuela

This interesting novel about the Mexican Revolution is cynical toward everyone concerned. The main characters are peasants who become rebels. There are a lot of funny bits. The most depressing part is how the women are treated like garbage by everyone. You get the impression that the people of Mexico will get the shaft, no matter who wins. This is the first Mexican novel I have encountered in this project and I hope I will find more.

Herland by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

I like Herland even more than 1911’s Moving The Mountain, and almost as much as “The Yellow Wallpaper,” which I think is one of the finest short stories. Although Gilman is famous for being a feminist, I don’t think she gets as much credit as she deserves for being a speculative fiction writer.

Three male explorers hear of a country that consists only of women, so they decide to check it out, and with great trouble make their way in. Jeff is a tender soul who glorifies motherhood and believes in being a perfect gentleman to women. Terry is a handsome man about town, kind of rapey and full of himself, and he thinks women should be pretty and serve him. The narrator, Vandyck Jennings, is sort of in-between these two and in general presents a “rational” point of view.

They are amazed to discover a beautiful utopia populated only by women, with wildly different customs from their own. In this country they don’t have poverty, they raise their children communally, they wear comfy clothes, etc. Long ago, a volcanic eruption and slave uprising led to a group of women who were cut off from the rest of the world. A few of them were miraculously able to reproduce as the result of sort of an exalted mental state, and this ability was passed down through the generations. There are so many novels about all-female societies where this happens—Ammonite by Nicola Griffith and Jane Fletcher’s Celaeno series spring to mind—but Herland must be the first.

The women the three explorers meet are all strong, intelligent, athletic, good teachers, and able to get things done. They confound the explorers’ expectations at every turn because they have no idea how to “behave like women.” Gilman takes the gender binary away and everyone becomes a person; however, she certainly has a rosy view of how nice an all-female society, or any society, could be.

The three explorers each fall in love and insist on marrying their sweethearts, which the women agree to in order to humor them, although marriage is a meaningless concept to them. All this time there has been no romantic love in the country because, well, when the men are gone, it’s just impossible! But they haven’t been missing it.

Terry and his wife Alima don’t get along. He attempts to rape her, but she kicks him in the balls and summons help from her friend in the room next door. Terry is put on trial, and the local Over Mother sentences him to be sent back to the outside world, with his word as a gentleman not to tell anyone about their country. At first Terry is obstinate.

“The first thing I’ll do is to get an expedition fixed up to force an entrance into Ma-Land!”

“Then,” they said quite calmly, “he must remain an absolute prisoner always.”

“Anesthesia would be kinder,” urged Moadine.

“And safer,” added Zava.

“He will promise, I think,” said Ellador [Jennings’ wife.]

And he did.

(This part reminded me of Houston, Houston, Do You Read? by James Tiptree, Jr.)

So Terry leaves, with Jennings and Ellador to escort him. Next year is the sequel! From Gilman’s Wikipedia page I learned a lot of things that I didn’t know about her, including the fact that she married her first cousin, and that when she was diagnosed with incurable breast cancer she “chose chloroform over cancer” (her words.)

The Scarecrow of Oz by L. Frank Baum

I love all the Oz books! This is the one in which a little girl named Trot and her sailor pal Cap’n Bill come to Oz. They meet a lot of lovable characters like the Bumpy Man and Button Bright, and they help the Scarecrow solve a problem with the monarchy of Jinxland.

World War I

Of Human Bondage

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Natsume Soseki

Baroness Orczy

TS Eliot

maugham

Herland

antiwar

Antisemitism

l frank baum

best of 1915

books of 1915

girl least likely to

love song of j alfred prufrock

the wasteland

do i dare to eat a peach

grass on the wayside

bride of the plains

the underdogs

los de abajo

mariano azuela

the scarecrow of oz

carpathian basin

World War I

Of Human Bondage

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Natsume Soseki

Baroness Orczy

TS Eliot

maugham

Herland

antiwar

Antisemitism

l frank baum

best of 1915

books of 1915

girl least likely to

love song of j alfred prufrock

the wasteland

do i dare to eat a peach

grass on the wayside

bride of the plains

the underdogs

los de abajo

mariano azuela

the scarecrow of oz

carpathian basin

Books of 1915 (Part One)

I'm a little late with my reviews of the books of 1915! Then again, what's really the difference between a century, and a century and ten weeks?

The Song of The Lark by Willa Cather

I’m going to go out on a limb and say this was the best novel of 1915. When I told my brother I was reading The Song of The Lark, he said he had read it too, after he had read a mention of it in an article by Arlene Croce saying that it was one of the only novels about the development of a young girl into an artist. I was curious exactly what kind of zingy one-liner had entranced my brother into reading this book, so I looked up what Croce said specifically, and it was in a review of the dancer Suzanne Farrell’s autobiography. “Holding On to the Air isn’t really the inside story of Suzanne Farrell and George Balanchine. The real inside story would take a writer of Willa Cather’s stature to deal with. In The Song of the Lark, Cather’s novel about a girl from a prairie town who becomes a great Wagnerian soprano, we discover the true dimensions of a life lived for art.” I do wish that I got to read more often about a girl developing into a great artist. In addition, the main character was a florid example of Enneagram Type Four, my favorite type, which I just loved.

The protagonist, Thea, is a Scandinavian-American girl living in a no-account town in Colorado. She has always felt that she is different from everyone else, and is fiercely sensitive and beset by envy. She is taking piano lessons from a decrepit alcoholic who was once a brilliant pianist, and it is understood that when she is grown she can make her living as a piano teacher herself. The town doctor is her closest friend and confidant. There’s a freight train conductor, Ray, who is in love with her even though she’s only eleven. Cather manages to convey this as sort of sweet but I still couldn’t help reading it as creepy. However,

(show spoiler)Always in her heart she’s thought of herself as a singer, but she’s too independent-minded and it’s too precious for her to discuss it. However, when her piano instructor finally hears her sing, he sets her on another path.

Although Thea is very single-minded about her art, she does fall in love at one point with a rich young man. Unfortunately

(show spoiler)Willa Cather writes about this guy like she likes him, but I don’t. I do get the impression that Cather finds it hard to take romantic love between a woman and a man very seriously. Anyway, the rich beau does remain very loyal to Thea, and so does her doctor friend.

One thing that’s really notable about this book is how not-racist it is, compared to most of the books of 1915. As a girl, Thea likes to hang out with the Mexicans who live in her town, especially Spanish Johnny and the other musicians. These characters and their music are described with seriousness, individuality, and respect. (I don’t think she achieved this high standard in all her books, though. I’m not looking forward to Sapphira and the Slave Girl, Cather’s last novel, but maybe by 2040 I’ll be too old and decrepit to review books.) Anyway, Cather’s descriptions overall are marvelous. They have a poignant quality, making me feel as if she’s depicting my own self, when nothing could be farther from the truth.

What I remember best about this book is a long conversation my wife and I had about the following passage about childhood and having a rich inner life:

“But you see, when I set out from Moonstone [her hometown] with you, I had a rich, romantic past. I had lived a long, eventful life, and an artist’s life, every hour of it. Wagner says, in his most beautiful opera, that art is only a way of remembering youth. And the older we grow the more precious it seems to us, and the more richly we can present that memory. When we’ve got it all out,—the last, the finest thrill of it, the brightest hope of it,” she lifted her hand above her head and dropped it,—“then we stop. We do nothing but repeat after that. The stream has reached the level of the source. That’s our measure.”

When I was looking for the Arlene Croce quotation online, I found a lot of other strange quotations about Willa Cather. People have many weird things to say about her. For example, in an extremely transphobic and unreadable 1997 New Yorker article, the author speculates that Willa Cather would have been “impatient” with Brandon Teena and considered his “gender confusion” as “self-indulgent.” I think of all the authors of this time period, Willa Cather would be the least likely to be a hater, but obviously no one including me has any idea what she thought (or would have thought) about something that didn’t have a name in her time period. Gore Vidal in 1992: “(Willa Cather) liked men to be men, and women to be men, too. She seemed unaware of the paradox.” Huh? It seems that Willa Cather conjures up some very strong ideas in people’s minds and she is still kind of a lightning rod when it comes to gender.

Something Fresh by PG Wodehouse

This is hands-down the funniest novel of 1915. All of Wodehouse’s novels are hilarious. Probably the reason I didn't crown this one as the best novel is a terrible societal prejudice against comedy. This one is in the Blandings Castle series, where people end up at the country home of kooky Lord Emsworth, none of them who they are pretending to be. This time, the heroes are two young struggling but spirited writers, a woman and a man, who both become enmeshed in the quest to steal back an Egyptian scarab that Lord Emsworth has absentmindedly walked off with. There are a number of delightful subplots and love plots, and several characters have health problems with the lining of their stomachs. The only thing that was at all tough about this marvelous novel is that the details of all the imposters are so intricate that when I put the book down for a week I had trouble remembering what was really going on when I picked it back up.

The Forged Note: A Romance of the Darker Races by Oscar Micheaux

This was one of my favorites of 1915. It was different from all the others in several ways, the most obvious and notable one being that it was written by an African-American author. So as I opened it up I was really rooting for it to be good. I was a little perturbed by the dust jacket copy, which was a perplexing diatribe describing how the author had been cheated out of his homestead by his ex-wife and ex-father-in-law, very similar to the kind of off-the-wall, off-topic back cover copy you might get on some contemporary self-published books. This contretemps with the homestead involved a forgery, so from the title it looked like this would be the plot of the book. But it became clear that the homestead-marriage-forgery had all been covered in Micheaux’s previous novel The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer (which I should have read in 2013 but didn’t because 2013 was such a hard year.) It also became clear that although the hero of The Forged Note has a different name from the hero of The Conquest, this is basically a sequel, and very closely based on Oscar Micheaux’s real life. So, for example, the hero of The Forged Note is an author whose ex-wife and her father conspired against him, and he is now engaged in selling his first novel. Confusing? Yes! Meta and interesting? Yes!

Micheaux has a very engaging style and describes things in a witty way. The main character, Sydney Wyeth, travels to different cities to sell his novel to the black community. He does very well selling it door-to-door to domestic workers and other people with humble jobs, but it angers him that the intellectual leaders like teachers rarely buy his book. He thinks they’re a bunch of hypocrites, and even worse are the pastors, who are depicted as a bunch of ignorant power-hungry men who only seek to aggrandize themselves. (Although there’s also one good pastor character to act as a foil.) Even though Sydney is very clean-living, he finds petty criminals who get drunk and gamble away all their money amusing and good company. These characters, who would be the villains or jokes of other books, are three-dimensional, realistic, charming people.

Because Sydney is so handsome, a number of women are interested in him, but he keeps thinking of a woman he knew that he had to give up because of a shocking secret he learned about her. Meanwhile, far away, too-sweet-for-this-world Mildred can’t stop thinking about Sydney, so she sets out to sell his book as well.

Sydney is a close observer of human nature, and he sees a lot of interesting things. Like so many of these old books, the things that are most fascinating to a modern reader are too ordinary for the author to even make note of. And there were a couple of places where I could not understand what was going on. Unsurprisingly Micheaux paints a grim picture of Jim Crow cities. Black people aren’t allowed to use the library, playgrounds, or community centers so there’s literally nothing for kids to do. Lynchings are mentioned casually, and the police arrest black people for being out on the street at night. This happens to Sydney, and when he goes to his court date, he is thrown back in jail for being articulate and insufficiently cringing. The lesson this character takes from this is that he should never show up at his court date and just say goodbye to his bond money. To me it seemed like a lot of this stuff is unpleasantly relevant to today.

Sydney (and Micheaux) have no interest in white racism or why it exists or whether it might be overthrown; it’s just a force of nature that’s part of the landscape. One of the other characters, a newspaper editor who like Sydney seems to be a mouthpiece for Micheaux’s views, says that white people will always hate black people and that’s just the way it is. Instead, Sydney/Micheaux was hung up on the idea, which seems completely bonkers to a modern reader ie me, that the black people weren’t working hard enough. For example, in one of the cities (I forget which one because they all had pseudonyms) there was a movement to open either a library or a YMCA for African-American people. A Jewish donor promised a sum of money but only if it were matched by an equal sum. The churches were apathetic and didn’t raise nearly enough money. Sydney is enraged by this and writes an editorial in the paper talking about how lazy and no-good the black people of this city are. He leaves town immediately because he knows everyone will be mad, and I don’t blame them. Talk about kicking people when they’re down! At this point I really lost patience with Sydney. I think he’s an Enneagram Type 1 so he has a lot of great qualities but he also has a stick up his butt and he thinks he’s always right and that everyone should be like him.

But it’s really interesting to read what is basically a civil rights story that’s actually from the time period. I feel like when I read these things framed as historical narratives, it doesn’t show the in-fighting and batshit craziness and sense of hopelessness that I get from this novel, and I know those are all characteristics of present-day activism. Also, when I was discussing this novel with my wife, but talking about it as if it were science fiction, she said that if her life were completely circumscribed by weird aliens who hated humans, she wouldn’t be mad at the aliens either, she would just be mad at her fellow humans, so maybe Micheaux’s response is more natural than I thought.

As far as the library/YMCA goes, Mildred saves the day by donating the missing amount of money, which was something like $10,000 that she made selling books. But various characters express doubt whether the library/YMCA will even make any difference or if the community will even appreciate it. Oy! By the way, everyone and everything in The Forged Note has a pseudonym. W.E.B. DuBois is called Derwin, and The Crisis is called The Climax. I forget what Booker T. Washington is called; I should have taken notes. I think Atlanta is called Attalia. Leo Frank is called “The Jew.” :( (That whole part was depressing.)

At last,