brokenbiscuits

I read this book for my “Best of 1913” project, but I have more than a few sentences to say about it. Why is this masterpiece completely forgotten while people are reading all this garbage by William Faulkner? Could it be the clanking, undying machinery of sheer sexism?

Virginia tells the story of a woman who lives in the ignorant backwater of Dinwiddie, Virginia. It opens in the 1880’s when Virginia has just graduated from the Dinwiddie Academy for Young Ladies and she’s eager to fall in love and enjoy life to the fullest. Ellen Glasgow paints a very compelling picture of a town whose white citizens are willing to lay down their lives for Southern ideals a) which they don’t understand and b) the ideals are completely stupid. Still, Glasgow likes these benighted people and presents them as loveable. I really did feel for these characters. Virginia has received a terrible education that was designed to make her obedient and well-mannered, and she doesn’t realize that she shares the fate of her mother and all the other women she knows, of throwing her life away in service to some man. Then she crosses paths with the first young man she has ever met who is handsome, intelligent, and not her cousin. (This has been a common theme of the books of 1913 that I’ve read so far—marrying the first eligible man you lay your eyes on. We are so lucky that today we get to meet lots of people and do ordinary things like go to school with them.) After Virginia and her beloved meet five times, they become engaged.

The man in question, Oliver, is an interesting character. He’s from out of town and he’s different from everyone in Dimwittie because he believes in art and science while they believe in Christianity, how awesome they were during the Civil War, keeping up appearances, and making a buck. His greatest dream is to be a writer; he scorns money and working; and he reads things like The Origin of Species. Although he’s intelligent and original, he’s also very selfish and basically has no empathy or insight into other people’s feelings. Don’t we all know people just like this? What a fully realized character! He resists falling in love with Virginia because he can see that supporting a wife will hamper his wannabe Bohemian lifestyle, but then he succumbs, and so he has to take a normal job and become interested in making money, just like everyone else. Throughout the novel he writes plays, which at first are complete flops. Then he decides to sell out and pander to the tastes of the Broadway audiences, and by the end of the book he has become an incredibly successful playwright, but he scorns his own work. I thought it was very clever of Ellen Glasgow not to even get into the question of whether Oliver’s writing is any good or not. She presents his POV and just leaves it at that.

Ultimately the portrayal of Oliver is of a person who has all these great qualities but is emotionally stunted to the point where he basically has no connection to his wife and children, yet he is in the typical range of males. Based on what I see in Redbook magazine, this problem is as prevalent today as it was a century ago. Virginia, meanwhile, is ignorant on every subject and isn’t curious about the world and has no time for rational thinking, but she can see with extraordinary sensitivity an entire realm of human psychology that is a closed book to Oliver. He’s impatient with her because all she cares about are her children and making the house look nice and managing the servants. He also gets cross that she doesn’t dress nicely anymore and has allowed her hands to get rough and coarsened—even though this has only happened because she’s been scrimping and pinching to make ends meet. Apparently the Southern gentlewoman wasn’t supposed to do any actual housework herself, but when she was too poor to afford servants she was supposed to do all the work secretly and still manage to look dainty and fresh.

The foil to Virginia’s simplicity and self-effacing nature is her best friend, Susan. Susan is naturally curious and forceful and thinks for herself. Her dream is to go to college, but her father won’t hear of it. (“Father, I want to go to college.” “If you want something to occupy you, you’d better start about helping your mother with her preserving.” “I put up seventy-five jars of strawberries.” “Well, the blackberries are coming along.”) To make the parallel exact, just as Oliver chooses a wife who is not his intellectual equal, Susan loves John Henry, a stolid, dull-witted man. But Susan and John Henry seem happy together and neither of them goes running around with fast actresses. Susan fills her life with charities and public movements and reading books. It seems to be enough.

(Virginia and Susan really are good friends! Listen to this:

“Promise me, Jinny, that you’ll never let anybody take my place,” she said, turning when they had reached the head of the steps.

“You silly Susan! Why of course they shan’t,” replied Virginia, and they kissed ecstatically.

“Nobody will ever love you as I do.”

“And I you, darling.”)

(But don’t worry, Virginia and Oliver’s love gets equal time:

“The world stopped suddenly while a starry eternity enveloped them. All youth was packed into that minute, all the troubled sweetness of desire, all the fugitive ecstasy of fulfilment.” You think they’re doing something really naughty, but actually it’s their first kiss.)

OK, I’m making fun of an overblown love scene, but they’re hard to do, and I really admire Ellen Glasgow’s writing. I wish I could write like her. Not just that I wish I could write such wonderful descriptions and could chivvy the plot along like she does while revealing meaningful things about the human condition. I wish I were “allowed” to write like her, with an omniscient third person narrator that tells you what’s right and wrong while letting you to see into the character’s hearts. If only that were still the fashion!

The one clunky part of the book was a transition when Virginia and Oliver are moving back to Dimwittie after an absence of five years, and we’re brought up to speed with dialogue like, “Isn’t it beautiful that her marriage has turned out so well?” I thought the most affecting parts were when Virginia’s mother dies (sorry for the spoiler. . . no wait, I’m not sorry) and when her son is very sick. Glasgow rips aside the veil and shows us that there’s little or no meaning to life but still we have to march along and invent meaning if we can. One of Virginia’s daughters leads a very different life from her mother because she goes to college, loves learning, has “modern ideas,” and scorns the feminine tradition of self-sacrifice. Too bad she’s also completely selfish and doesn’t care about her mother. Glasgow portrays the daughter’s modern views as correct but too late and of no help to someone like Virginia who is mired in tradition. Although the novel’s ending is grim, I was glad there was a ray of hope for Virginia.

The Achilles heel of this novel is exactly what you would expect of a novel about Southern life in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century: racism. When describing the African-American characters (all minor characters), there’s a lot of “primitive” this, “savage” that, “wild animal” this, such-and-such “creature.” Also some speech rendered in offensive dialect and one use of a racial slur (in dialogue or maybe a letter, not from the narrator’s POV.) The sad thing is that clearly Ellen Glasgow was liberal-minded and held the progressive views of her day, when a big civil rights issue was trying to get someone in power to do anything at all to stop lynching. So basically this kind of racist claptrap was as anti-racist as a book by a white person got at the time.

Here’s a spoiler for you—Virginia’s father dies preventing a lynching. No one lionizes him for it, and it may be that none of the white characters even know what happened. Just as Virginia has Susan as her opposite number, Virginia’s father has Cyrus Treadwell as his foil. They were buddies in the Civil War but while Virginia’s father is good and spiritual, Cyrus Treadwell is mean and greedy. An African-American washerwoman, Mandy, keeps appealing to Cyrus Treadwell to help her, the subtext being that he is the father of her son, conceived when she was a fifteen-year old servant in the Treadwell house in 1866. This is depicted so subtly that I wondered if I was imagining it until later in the book when it becomes slightly more explicit. Clearly Glasgow wants to condemn abusers like Cyrus Treadwell but the topic is too hot for her to approach it directly.

In conclusion, I thought this book was terrific and I think it deserves a greater reputation than it has. A lot of other books (by men) with some creepy racist elements are still regarded as worth reading so why not this one? I read the Penguin Classic edition and after I was done I read the introduction, which was, as always, somewhat bananas. This academic, in 1989, really thought it was totally fine to use the word “mulatto”? But I learned a few interesting tidbits about Ellen Glasgow and her family. Her sister Cary led a cheerless existence and after her husband (and her brother) died by suicide she devoted her life to reading books her husband had liked so that when they were reunited in the afterlife they would have something to talk about. Whaaat? But then I thought about it some more, and it makes as much sense as anything else. What are you supposed to do in that situation? Why am I reading the books of 1913? Why does anyone do anything?

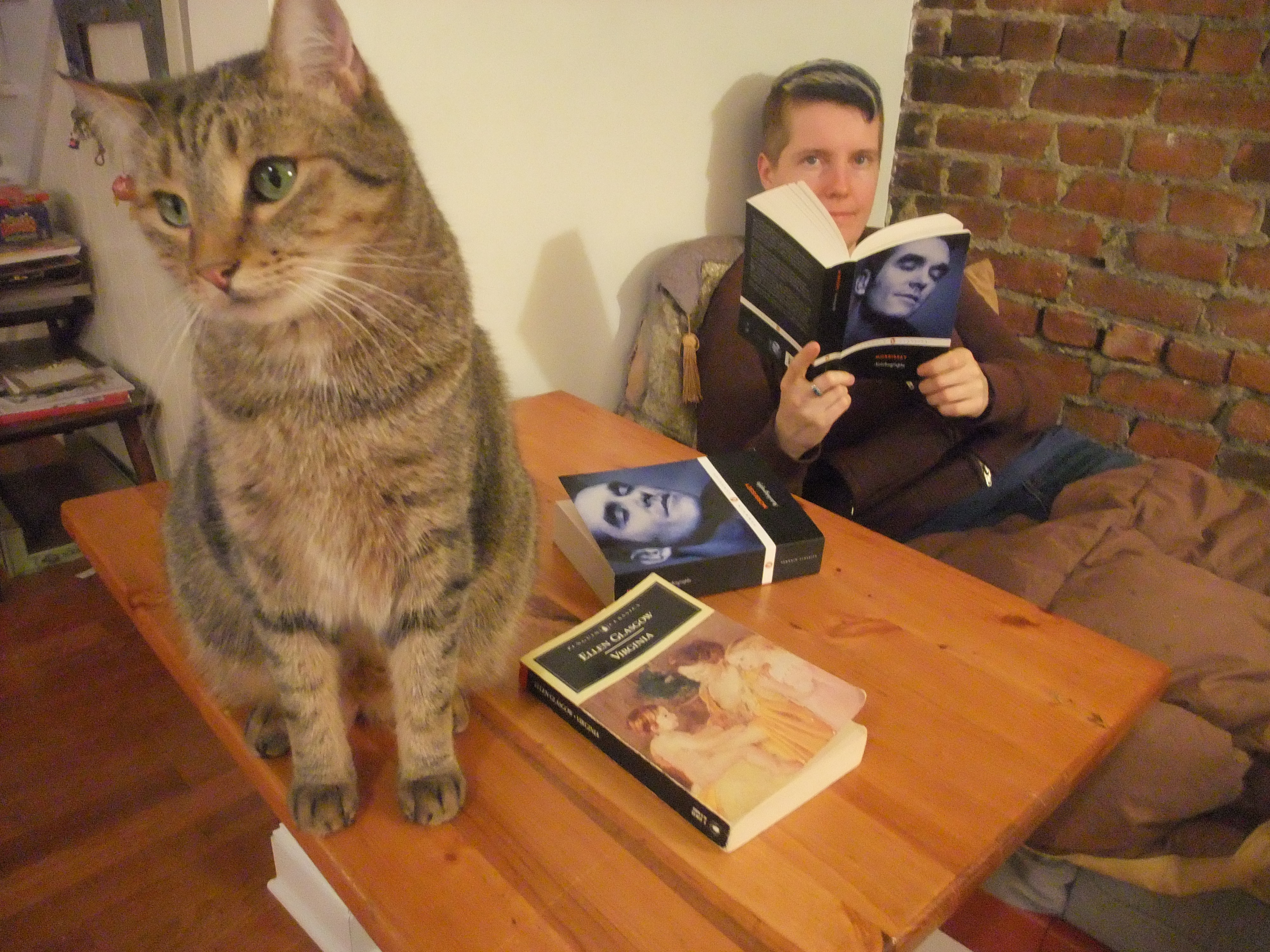

Book design and all that: It looks like all the Penguin Classics of the pre-2002 template with the red top of the spine that means it’s in English. The cover art, a painting by Mary Cassatt, is very appropriate. Some typos.

Other book similar to this: The Life and Death of Harriet Frean by May Sinclair.

Theme song: The Ballad of Lucy Jordan by Marianne Faithfull